Agnese Leonello, Caterina Mendicino, Ettore Panetti, Davide Porcellacchia

Review of Finance, Volume 29, Issue 2, March 2025, Pages 501–530, https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfae045

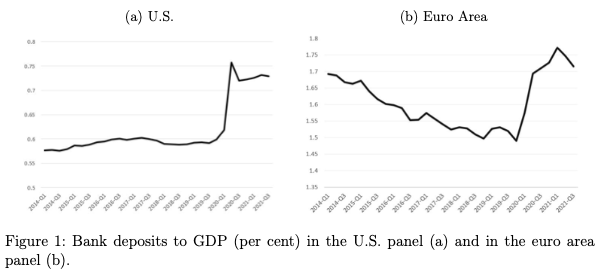

In recent years, banks have experienced unprecedented growth in deposits, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the U.S., total bank deposits as a percentage of GDP surged by around 15 percentage points in the first quarter of 2020, while the Euro Area saw an increase of approximately 20 percentage points. While this inflow provided short-term bank liquidity, it possibly contributed to build up conditions that triggered recent failures, like that of Silicon Valley Bank in 2023. This paper investigates the implications of rising deposit levels on bank stability and economic efficiency, offering insights into how these dynamics contribute to financial fragility.

The paper extends the classic bank-run framework (e.g., Goldstein and Pauzner, 2005) by introducing a consumption-saving decision. Investors allocate their initial endowment between immediate consumption and deposits in a bank. Banks invest deposits in a long-term project but face the risk of early withdrawals due to coordination failures among depositors. The model features three main ingredients: (i) risk-averse investors with idiosyncratic liquidity needs, (ii) imperfect information about economic fundamentals and (iii) strategic complementarities in withdrawal decisions: depositors, fearing others will withdraw, may preemptively withdraw their own funds, thereby making the bank go bankrupt.

Our findings highlight a positive relation between the level of deposits and the probability of bank runs, in that a higher level of deposits increase depositors’ incentives to run. Individual depositors fail to consider this effect in their saving decisions, in contrast to what a social planner would do. Consequently, the decentralized equilibrium is inefficient. This “saving externality” leads to over-saving as well as exceedingly large banks, excessive financial fragility, and an inefficient provision of bank liquidity.

The inefficiency caused by the saving externality suggests a role for public intervention. Fiscal policies, in particular a proportional tax on deposits, could resolve the inefficiency by aligning individual saving decisions with the socially optimal level. The deposit tax is proportional to the marginal effect of deposits on the run probability and the utility loss from runs, and has the effect of discouraging overly large banks, reducing financial fragility, and restoring constrained efficiency.

This study contributes to the literature on bank fragility, financial intermediation, and policy design by highlighting a previously overlooked externality in saving decisions. From a policy perspective, it also underscores the importance of integrating prudential and fiscal policies to address financial fragility in a comprehensive manner.