Large Bets and Stock Market Crashes

Albert S Kyle and Anna A Obizhaeva

Review of Finance, Volume 27, Issue 6, November 2023, Pages 2163–2203, https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfad008

After stock market crashes, market participants, policymakers, and economists are usually unable to explain what happened. Heavy selling pressure has been recorded during crashes. It is known that large imbalances move prices in the direction of trades, but there is no compelling quantitative explanation for why the seemingly small quantities sold might have led to such large price dislocations in the highly liquid stock market.

We investigate this issue through the lens of market microstructure invariance, a conceptual framework developed Kyle and Obizhaeva (2016).

By analyzing prices and quantities in market-specific business time rather than in calendar time, we are able to explain why seemingly small imbalances in demand and supply of observed sizes were indeed outliers that could have created such big market crashes.

We illustrate our approach by studying five crash events: the market crash of 1929, the market crash of 1987, the trades of George Soros in 1987, the liquidation of fraudulent positions at Société Générale in 2008, and the flash crash in 2010.

Figure

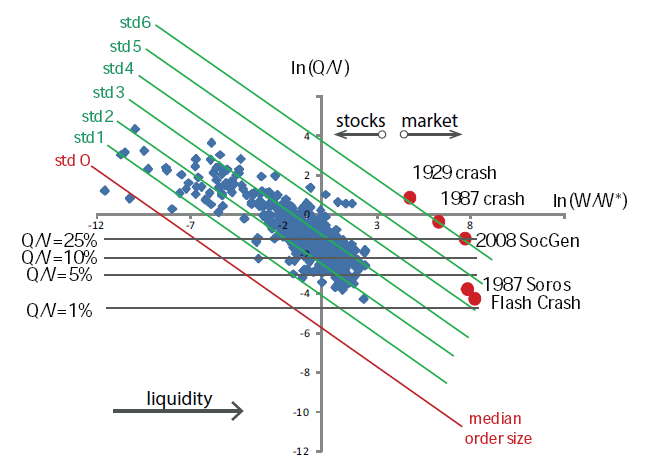

The figure summarizes the intuition of our paper in one snapshot. The vertical axis shows sizes of imbalances in demand and supply as a function of market liquidity for five crash episodes (in red) and a set of large institutional orders routinely executed in the market (in blue). The horizontal axis plots liquidity of the corresponding markets, ranging from markets for illiquid individual stocks on the left to very liquid markets for index futures on the right.

The conventional intuition and invariance framework differ from each other in how these theories extrapolate liquidity across markets. According to conventional intuition, which extrapolates along horizontal lines, imbalances during five crashes were not extraordinary large comparing to large institutional orders and they were expected to trigger relatively insignificant price changes. According to the invariance hypothesis, which extrapolates along lines with slope -2/3, imbalances during crashes were large outliers and they were expected to trigger large price dislocations quantitatively comparable to those observed in reality.

Our study further offers several practical insights about why stock market crashes happen, how to prevent them if possible, and how to respond to them if they occur. Large price dislocations may occur because of significant imbalances in demand and supply. Even in highly liquid markets and even if quantities traded are restricted to five or ten percent of daily volume, execution of large bets may lead to significant price changes. Rapid execution is likely to magnify transitory impact. Heavy selling in one market is likely to spread to economically related markets. Policies aiming at easing flow of credit and providing funds to make up the gap in demand and supply may help to mitigate the adverse effects of crashes, but the amount of funds necessary must be comparable to the size of the shock itself. Early warning systems may potentially help to prepare for crashes and act accordingly to mitigate or avoid them.