Teng Liu, Brook Constantz, Galina Hale, and Michael W Beck

Review of Finance, Volume 30, Issue 1, January 2026, Pages 87–129, https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfaf061

Climate change is no longer a distant threat. Extreme weather events, such as hurricanes and floods, are becoming more frequent and more severe. While we must continue to work on mitigation (reducing greenhouse gas emissions); it is increasingly imperative to advance adaptation and help protect people, property, and nature from the impacts that are already here and growing.

Two effective adaptation strategies are to protect and to restore coastal wetlands, like mangrove forests. Mangroves act as natural barriers, reducing flooding from storms. Yet, the financial value of these natural defenses can be hard to measure, which makes it challenging to attract private investment. This matters because public funding alone is not enough to meet the growing need for nature conservation and climate adaptation.

In our research, we evaluate private economic benefits of mangroves by studying how they affect home prices along Florida’s coastline. Prior studies estimated the financial benefits of mangroves only from the direct effects of avoided damages during storms. We analyzed variation in the decline in the value of coastal properties across the State after hurricane seasons. Using variation across repeated sales of the same properties over time, over a million transactions in total, we find that home values drop after hurricanes, but the decline is much smaller for properties near mangrove forests. After removing effects from many potential confounding factors, we show the value that buyers and investors put on the storm protection benefits from mangroves.

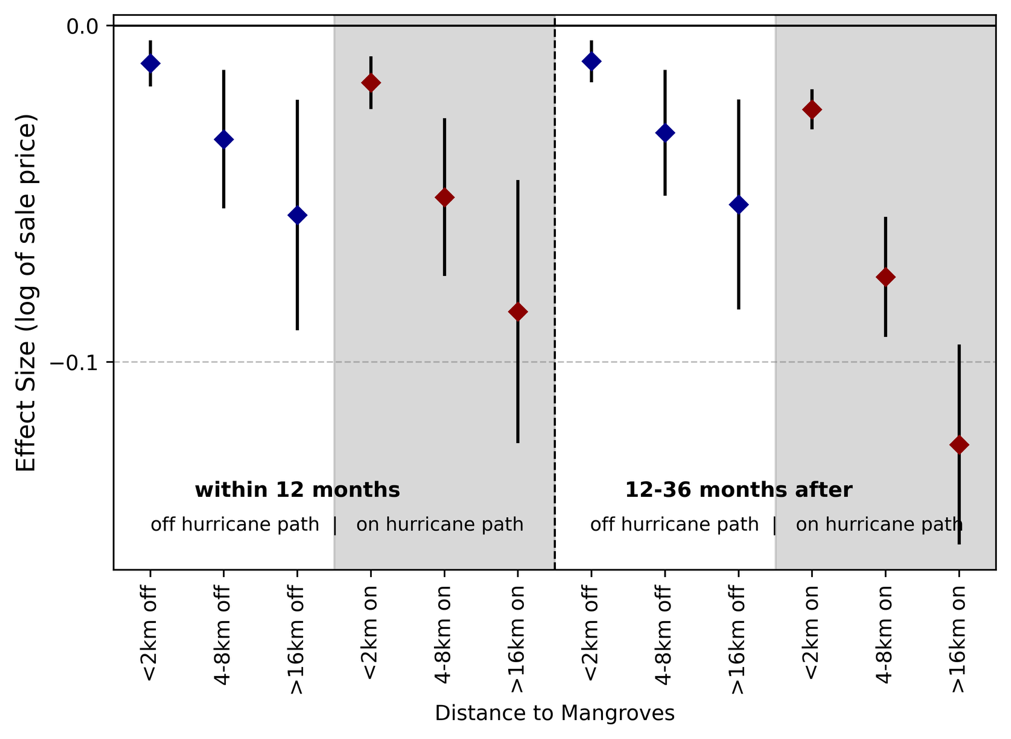

Our quantitative results are summarized in the Figure which shows that property price decline following hurricanes is larger for properties further away from mangroves. This effect is persistent over time and is also apparent for counties that are not on the hurricane path, which means that housing market participants recognize the value of protection mangrove forests provide even in the absence of direct physical damages. The probability of losing 25 percent or more of housing value can be as much as 7 percentage points lower due to proximity to mangroves compared with properties that are not near mangroves: for example, in Collier county after hurricane Irma in 2017 the probability of 25% value loss is 36% for properties that are not protected by mangroves, but only 29% for properties near mangroves. Conditional on hurricane occurrence, this translates into 60 thousand dollars per 1-million-dollar house under standard assumptions, likely exceeding estimated direct damages or insurance premium differences.

Given that mangroves provide these benefits to residential property owners as well as developers, insurance companies, and financial institutions, these private agents have a financial interest in investing in the protection and restoration of mangroves. When combined with many other benefits of mangroves — flood protection of agricultural areas, fisheries, public infrastructure, open spaces, and other properties, carbon sequestration potential, as well as biodiversity protection and other ecological benefits — public and private stakeholders need to work together to fund preservation and restoration of mangrove ecosystems.

Figure 1