Zoey Yiyuan Zhou, Douglas Almond

Review of Finance, 2025;, rfaf066, https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfaf066

Voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) are often promoted as a win-win—delivering both climate mitigation and biodiversity protection through nature-based projects such as reforestation, avoided deforestation, and soil carbon enhancement. Yet despite these claims, little empirical evidence exists to confirm whether carbon offset projects actually improve biodiversity outcomes.

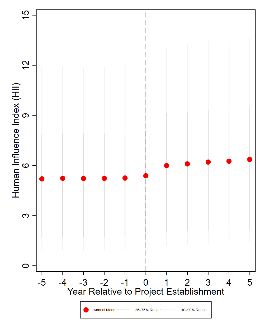

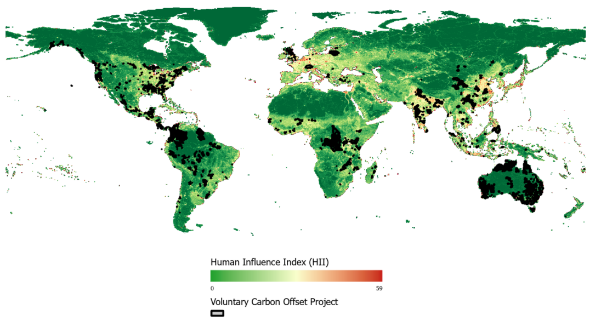

This research provides the first large-scale empirical assessment of biodiversity performance across global voluntary carbon offset projects. Drawing on a novel dataset of nearly 30,000 projects (about 2,700 with mapped spatial boundaries) and more than 419,000 carbon credit retirements, the analysis links registry records to satellite-based ecological indicators, including the Human Influence Index (HII), Biodiversity Habitat Index (BHI), and Bioclimatic Ecosystem Resilience Index (BERI). The goal is to determine whether carbon offset activities genuinely reduce human pressure on ecosystems or instead create unintended ecological trade-offs.

Key Findings

- No measurable biodiversity benefit: On average, carbon offset projects are associated with a 3.7% increase in human pressure on ecosystems, suggesting greater habitat disturbance rather than restoration.

- No positive effect for “biodiversity-labelled” projects: Even projects that claim biodiversity co-benefits or operate within protected areas show increased disturbance.

- Certification and ratings offer no ecological differentiation: Projects verified under major registries (e.g., Verra, Gold Standard) or rated by private evaluators such as BeZero, Sylvera, Calyx, AlliedOffsets, and Renoster perform similarly in biodiversity outcomes.

- Consistent evidence across indicators: Both BHI and BERI decline after project implementation, confirming that the results are not driven by any single metric.

- Hidden land-use trade-offs: Offset projects often convert shrublands and light forests into pasture, increasing carbon storage at the cost of ecological complexity and species richness.

- Post-2014 projects perform worse: Projects launched after the 2014 IPBES Global Assessment exhibit greater habitat degradation, suggesting limited progress despite growing awareness.

- Protected areas provide no buffer: Even within protected zones, offset activity correlates with higher human impact, questioning additionality and conservation value.

Contributions to the Field

This study delivers the first global-scale empirical test of biodiversity claims in carbon markets, moving beyond case studies and theory. It challenges the assumption that carbon sequestration and biodiversity benefits naturally align, showing instead a recurring trade-off between carbon efficiency and ecological integrity.

By combining financial datasets with remote-sensing biodiversity metrics, the research advances the emerging field of empirical biodiversity finance, linking environmental science and financial economics.

Implications

For investors, the findings reveal unpriced ecological risks in “green” assets. Carbon credits marketed as biodiversity-positive may, in practice, degrade habitats. Incorporating independent ecological data into ESG analysis and stewardship is therefore essential.

For policymakers, the results underscore the need for stronger biodiversity safeguards in carbon markets—through minimum ecological standards, land-use restrictions, and integration with credible policy and reporting frameworks. Strengthened monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems, supported by satellite-based ecological data, will be critical to align financial mechanisms with genuine environmental outcomes. As voluntary carbon markets grow toward a projected $50 billion valuation by 2030, their credibility will depend not only on carbon accounting but on verifiable biodiversity integrity.

Figure 1

Figure 2