Kim Fe Cramer

Review of Finance, Volume 29, Issue 5, September 2025, Pages 1497–1535, https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfaf032

What are the general equilibrium effects of banks on households? Previous research has focused on labor markets. Banks extend credit to firms, thereby fostering economic activity and employment. In this paper, I demonstrate that beyond that, bank presence can contribute towards tackling hard-to-crack development challenges, studying the third UN Sustainable Development Goal of improving households’ health. In addition to stimulating employment that allows households to invest more in health, banks may improve health through three distinct activities.

First, banks might offer savings accounts to households. Second, they may provide personal bank loans to households. Both savings accounts and bank loans could allow households to invest more in health when necessary. Third, banks could extend credit to healthcare providers, thereby stimulating healthcare supply, a crucial determinant of health status. Despite these strong motivations, we lack causal evidence on the impact of bank presence on households’ health.

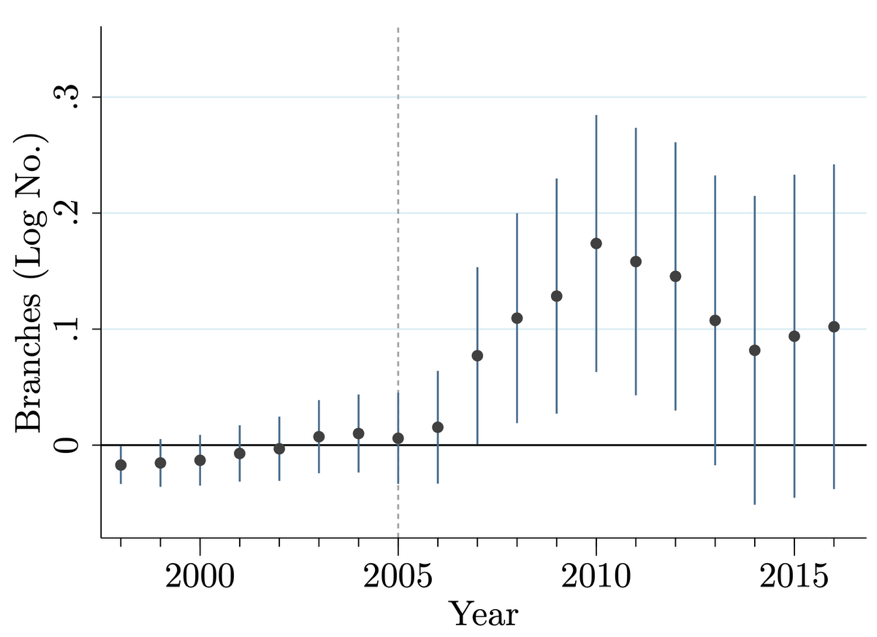

To obtain exogenous variation in bank presence, this paper utilizes a 2005 policy by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) that incentivized commercial banks to open new branches in underbanked districts. This policy allows for a regression discontinuity design, comparing districts that are just above and below a cutoff.

Five years after the policy’s implementation, treatment districts experienced a 19% increase in bank branches relative to control districts, equivalent to an average of 27 additional branches. This translated into an increase in employment, as well as more savings accounts for households. In alignment with these effects, I observe that households invest more in low-fixed-costs health investments and increase their healthcare demand. Critically, in alignment with the literature on credit constraints in developing countries, the average household does not gain access to personal bank loans.

On the healthcare supply side, hospitals in treatment districts utilized more credit, expanded their services, and contributed to a richer healthcare infrastructure. These results underscore the role of banks not only in supporting demand-side household investments in health, but also in enabling supply-side improvements via credit to healthcare facilities.

Crucially, these changes translated into tangible health improvements. Six years after the policy, households in treatment districts were 19 percentage points less likely to report a non-chronic illness in the past month. These results are consistent with other effective public health interventions and are validated in a second national survey conducted ten years post-policy. Chronic illnesses, which are less sensitive to short-term investments and require more sophisticated care, showed no significant change.

This study contributes to a growing literature on the general equilibrium effects of financial development. It offers evidence that bank presence can enhance not only economic outcomes but also households’ health, particularly by alleviating financial constraints that limit both household investments and healthcare provision. The findings have direct policy relevance: initiatives to expand financial infrastructure in underserved areas can deliver broad welfare gains, extending beyond employment to health and well-being.

Figure 1