Agostino Capponi, Albert J. Menkveld, Hongzhong Zhang

Review of Finance, Volume 29, Issue 1, January 2025, Pages 201–239, https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfae036

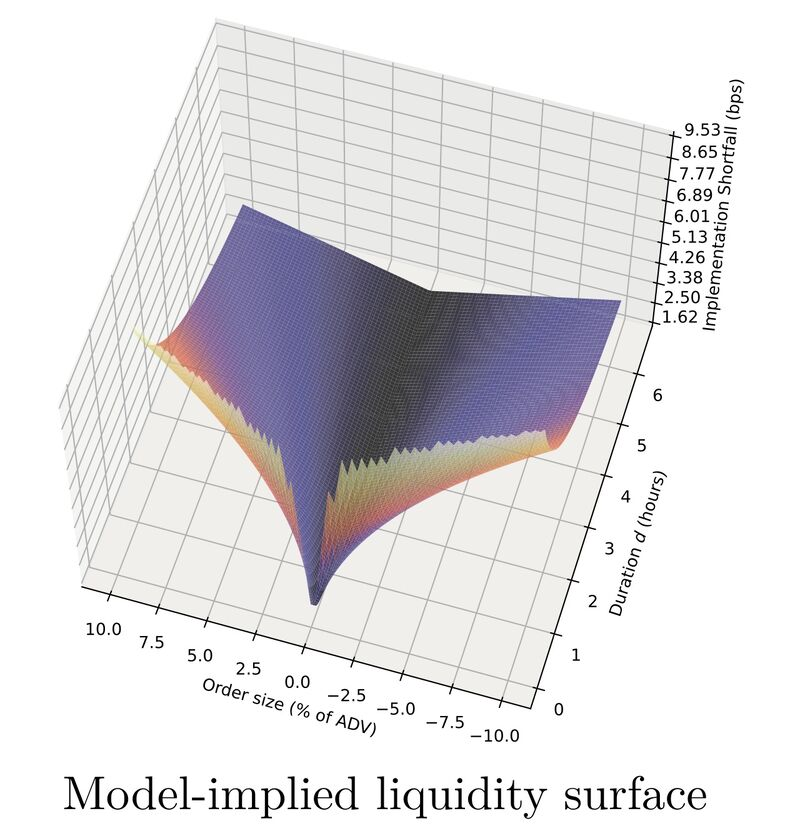

Institutional investors have become so large in many markets that their orders experience substantial price impact. In response, they started to algorithmically shred the order into smaller pieces that are sent to the market over a particular time interval. Transaction cost, therefore, has become a function of two parameters: the size of the order and its duration. Transaction cost for large investors becomes a three-dimensional object: a liquidity surface.

When optimizing, an institutional investor is mindful of the strategic response of market makers. These market makers solve a dynamic inventory model, whereby they effectively intermediate between the institutional investor and randomly arriving small investors. The price is endogenous; it is the outcome of a market-clearing condition. This equilibrium price is ultimately driving transaction cost of the institutional investor.

We model this environment in such a way that the equilibrium is tractable and yields analytic expressions. We calibrate it to real-world data to yield a liquidity surface for actively traded equities. One of the outcomes is an equilibrium liquidity surface that is included in this post. We further use the model to answer how the presence of a large investor affects welfare of other market participants. Do market makers benefit? And, more importantly from a regulatory perspective, do small investors benefit?

Our analysis contributes to a large theoretical literature on market liquidity, in which information is symmetric across participants. One set of models studies best execution in the presence of exogenous liquidity supply. Another set does the opposite. It assumes that liquidity demand is exogenous and endogenizes liquidity supply. We endogenize both sides in the sense that optimal execution is studied in a market where liquidity supply is endogenous.

Figure