The Revolving Door for Financial Regulators

Review of Finance, Volume 21, Issue 4, 1 July 2017, Pages 1445–1484,https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfw035

Public attention and media coverage often focus on the migration of employees between regulatory agencies and regulated firms. We investigate financial firms’ hiring of former US financial regulatory employees using a 2001–15 sample of executives with employment histories that include the Federal Reserve, the SEC, FINRA, the CFTC, the OCC, or the FDIC.

In this sample, the number of top executives with regulatory experience per firm has increased 24% over 2001–15. We find a positive 0.6% industry-adjusted average return on hiring announcement days, and a 0.8% return when we restrict the sample to top three executives and board members. In contrast, these firms do not show positive returns on average when other top-3 executive changes occur.

One potential explanation for the positive returns is that the ex-regulator is hired in order to obtain, or as a reward for, preferential treatment from the regulatory agency (the “quid pro quo” hypothesis). Alternatively, ex-regulators could be hired for their expertise (the “regulatory schooling” hypothesis), perhaps after receiving regulatory pressure to manage risk. The evidence we find is most consistent with the schooling hypothesis. In the quarter after an ex-regulator is hired by a regulated firm, the firm’s idiosyncratic stock return volatility is lower by approximately 7.5% of its mean over all regulators, controlling for other potential determinants of stock price volatility such as recent regulatory actions. Total volatility and measures of upside and downside volatility also decrease. When we examine why markets perceive firms to be safer, we find that firm leverage also decreases, along with Tier 1 capital ratios for firms that calculate them. One way that firms improve these ratios is through lowering their dividend payouts. The majority of these results are stronger for prudential regulators, who primarily monitor firms’ risk levels (The FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and the OCC) than for regulators whose primary focus is on policing markets (The CFTC, FINRA, and the SEC).

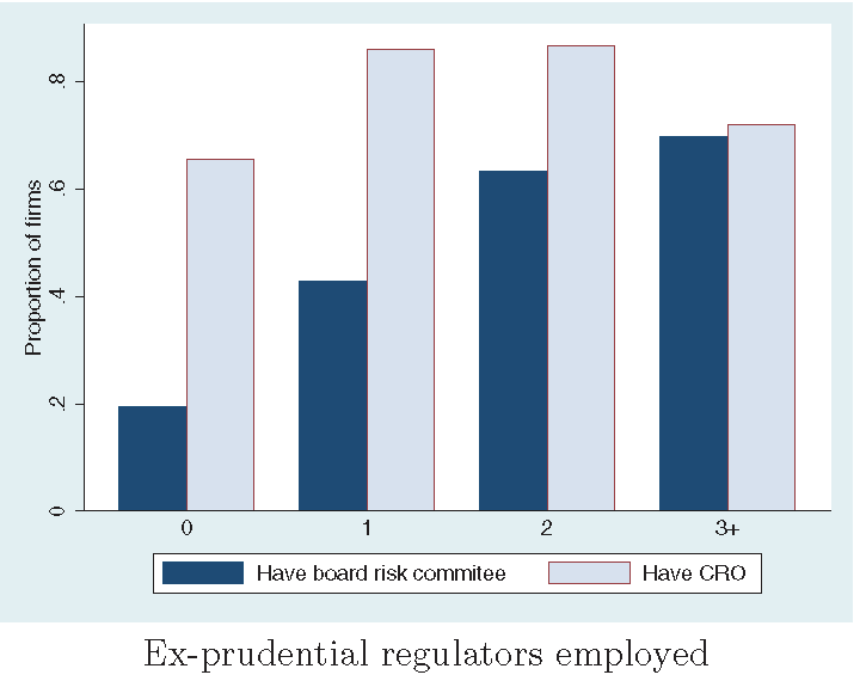

These results are not present when executives with no regulatory experience are hired by the firm or when a firm hires an ex-regulator from an agency that does not regulate it. The hire must also be voluntary on the part of the financial firm as there is no decrease in risk when a financial firm’s CEO exogenously acquires regulatory experience through being elected a Federal Reserve Class A director. We find that when ex-regulators are present at a firm, it is more likely to have a chief risk officer and a risk committee on the board. These results provide evidence that a frequent motivation for financial firm’s hiring of ex-regulators is the perceived necessity of improving the firm’s risk profile, perhaps at the request of the regulatory agency.

Last, we find scant evidence of decreased regulatory activity or lower fines in the 2 years before and after the hire of an ex-regulator. Since our measures of regulatory enforcement activity are restricted to publicly disclosed activity, we conclude only that if quid pro quo behavior is occurring, it is not flagrant.